Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), resolutely captures its audience’s attention from inception to present day. Scarcely few creative works stand the test of time so well as Mary Shelley’s novel, and this is a testament not only to her prowess as a writer but also the relevancy of her ideas across time. She crafted the epitome of mad scientists through Victor Frankenstein and a creature so horrifying as to be the inspiration for countless other monsters. Her story permeates the cultural imagination so thoroughly that even uttering “Frankenstein” calls to mind images of a grotesque figure on an operation table with stitches and deformities. This nameless monster captivates the mind and enthralls the senses of all who witness it, and his misfortune evokes an unlikely sympathy that intermingles with fear.

Mary’s Life

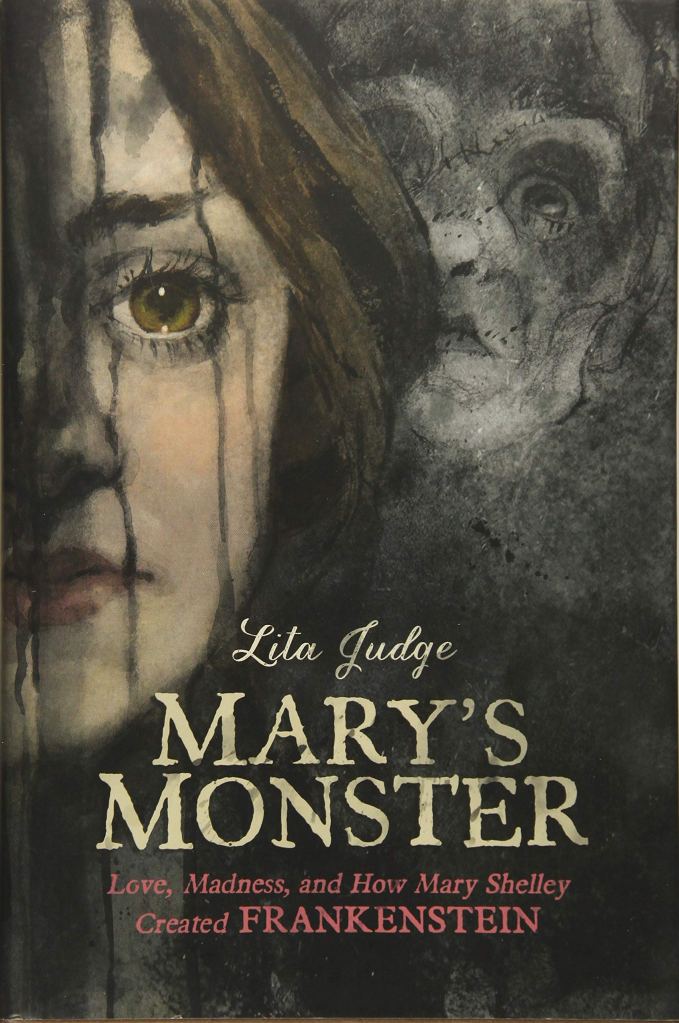

These fabricated misfortunes pale in comparison to Mary Shelley’s real-life hardships. Lita Judge, an author and illustrator of over a dozen picture books, showcased Shelley’s tragic life through her artfully crafted novel entitled Mary’s Monster: Love, Madness, and How Mary Shelley Created FRANKENSTEIN. Using black-and-white watercolors coupled with free verse poetry, Judge compiled the events of Shelley’s life into a cohesive narrative, underscoring her inspiration for and creation of Frankenstein. While Judge took some creative liberties, she based her poetry on Mary’s prose and illustrated her life in powerful ways.

Figure 1: Cover of Mary’s Monster (Judge, 2018)

Mary’s Mother

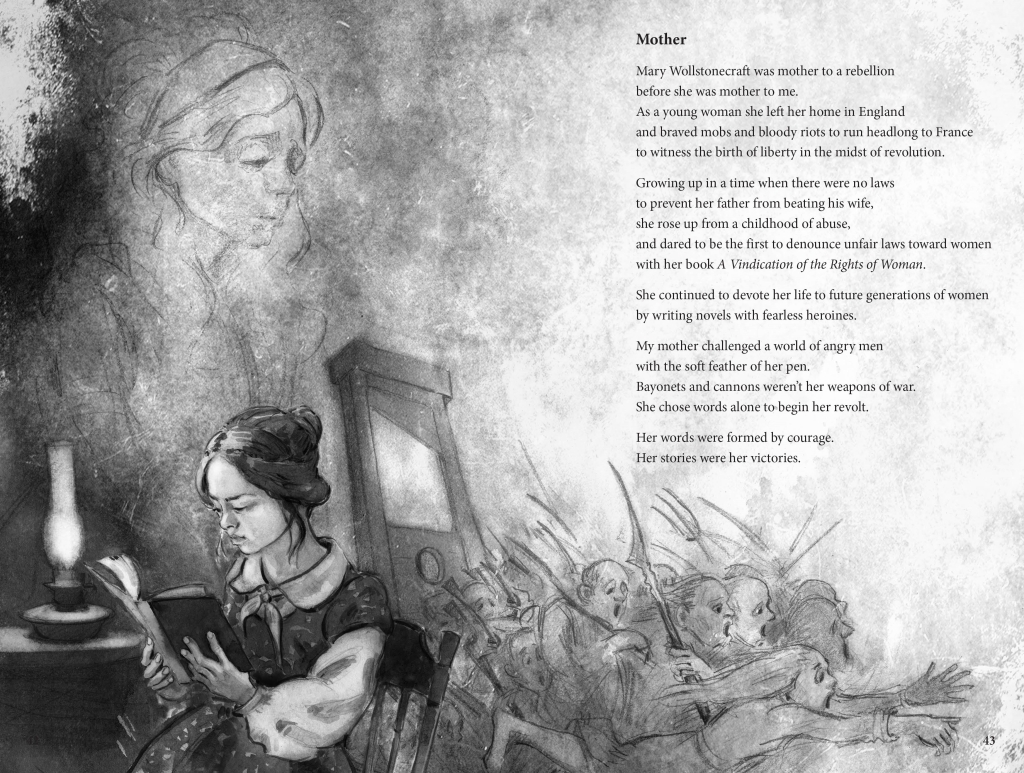

For the sake of her daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft sacrificed her life during childbirth. Reflecting on these ramifications, Shelley wrote “For ten days after my birth / my mother battled to live … But she no longer breathes, / because I do” (Judge, 2018, p. 32). In this way, Shelley expressed an immense sense of survivor’s guilt. What’s more, Shelley’s only way of connecting with her mother was through reading her painstakingly produced and politically charged writings. For instance, after reading Wollstonecraft’s Maria, Shelley exclaimed “Her thoughts and ideas reach across the space of time / and come alive and lodge inside my chest / like my own heartbeat” (Judge, 2018, p. 44). Despite her mother’s absence, Mary salvaged their relationship, illustrating words’ capacity to influence future generations.

Figure 2: Mary Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft (Judge, 2018, p. 42, 43)

Mary’s Father

William Godwin was hardly the conventional father. As a revolutionary and anarchist, Godwin asserted that liberty was attainable through the dismantling of tyrannical governments. Although many considered him to be a radical, Godwin instilled the importance of independence and imagination in his children. For instance, Mary recalled her father’s story of Caroline Herschel, a woman who pioneered her way into the male-dominated field of astronomy. Male astronomers disregarded her first discoveries, but Caroline was undeterred, working relentlessly. After naming her eighth comet, Caroline’s authority within the field became indisputable. In response to this story, Mary wrote “Father gave me the belief that I could do anything” (Judge, 2018, p. 16). William did not expect his daughters to take up sewing or playing with dolls; rather, he encouraged them to read and discuss matters of science, politics, and literature. However, as Mary gradually changed with age, so too did William’s disposition toward her. Reflecting on this shift in character, she wrote “Father promised / freedom, love, equality / for women. / But for me, it seems, / he has locked the door / to any future / beyond selling books” (Judge, 2018, p. 96). When Mary returned home after running away, her father rebuked and disowned her, destroying any chance they had at mending their relationship. While Godwin nurtured Mary in her youth, he became cold and despondent in her adolescence.

Figure 3: Mary Shelley and William Godwin (Judge, 2018, p. 58)

Mary’s Stepmother

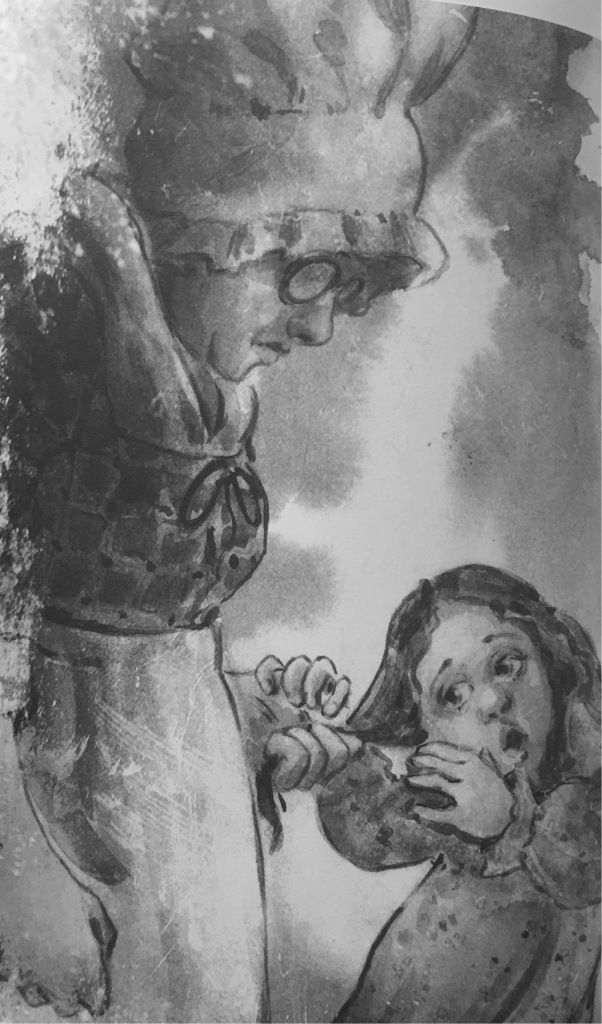

Shelley couldn’t fathom anyone filling a maternal role for her, yet Godwin found a replacement in Widow Clairmont, a woman who made even Cinderella’s evil stepmother seem tenderhearted. Mary Shelley described her first impression of Clairmont, stating that she “marched into our home looking / plump and pleased, / like a dog who has stolen another dog’s bone” (Judge, 2018, p. 20). Clairmont’s two children, Claire and Charles, weren’t far behind in step, looking just as confused as Shelley and her sister Fanny. The Widow became a fearful presence in the household. While Shelley was listening to her father’s friends tell stories, a favorite pastime of hers, she wrote that Clairmont “dragged me out by my hair / and hissed that I was an awful child” (Judge, 2018, p. 23). Shelley admitted her helplessness by writing “There was nothing I could do / except be silent and stare / when her anger poured over me” (Judge, 2018, p. 27). As Clairmont’s aggression escalated, however, Shelley confessed that “Father says nothing when Mrs. Godwin slaps me / so hard across the face my skin feels burned / and my bones bruised” (Judge, 2018, p. 94). This detestable abuse was business as usual under Widow Clairmont’s reign of tyranny.

Figure 4: Mary Shelley and Widow Clairmont (Judge, 2018, p. 22)

Mary’s Lover

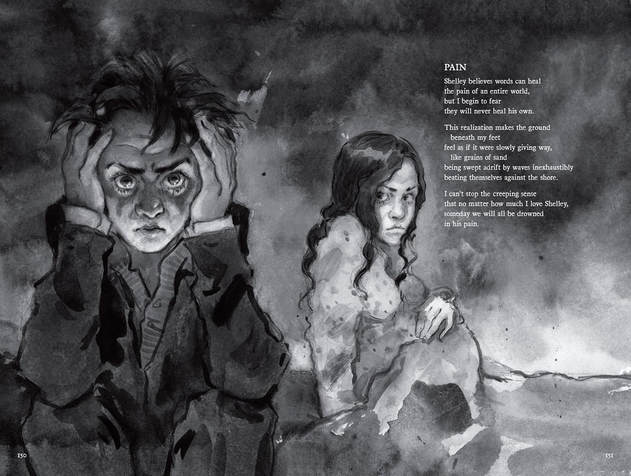

Just as Mary feared this toxicity would consume her, Percy Shelley entered her life, offering companionship and an avenue of escape. Upon their first encounter, Mary wrote that it was “as if a bolt of lightning / shoots through my soul” (Judge, 2018, p. 74). They quickly developed an affinity for each other, going on walks and engaging each other’s intellect with conversation. As their relationship blossomed, Mary soon realized that “like my mother and father, / who fought a revolution of ideas, / Shelley and I will fight our own / and set the world on its edge” (Judge, 2018, p. 91). Under the looming threat of parental discovery, they agreed to run away to Switzerland, concluding that being together mattered most. After running away, Mary witnessed poverty, famine, and squalor the likes of which she had never seen before. She sought comfort in Percy’s arms, but even this wouldn’t last. Mary was carrying Percy’s child, but, as fate would have it, the child would stop breathing shortly after birth. As if miscarriage weren’t enough, Percy became emotionally distant with Mary after the incident, choosing to pursue her stepsister Claire romantically. Mary wrote “Instead of remaining by my side, / Shelley and Claire walk out together / under blankets of apple blossoms, / leaving me alone and tortured” (Judge, 2018, p. 162). While Percy provided a support network for Mary, his love for her would prove fickle at the times she needed it most.

Figure 5: Mary Shelley and Percy Shelley (Judge, 2018, p. 150, 151)

Mary’s Loss

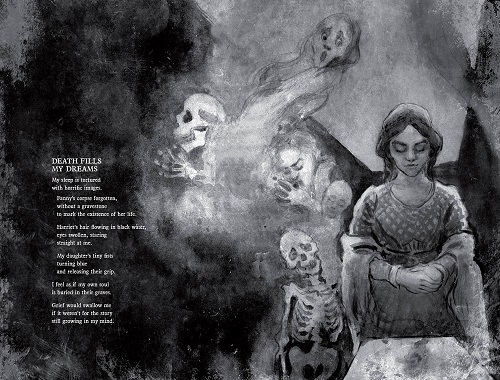

Mary experienced profound loss beyond her mother’s demise. After giving birth to Clara, Mary’s child would suffer breathing complications. Within ten days, Mary’s first child would die along with her hopes of motherhood. She described her devastation: “For ten days I cradle her in hope and joy / … But she was born too soon … I clutch her, helpless, when the convulsions come / to steal the life from her tiny limbs” (Judge, 2018, p. 158). Mary’s devastation would compound in 1816 when she discovered her sister Fanny had committed suicide. Mourning Fanny’s death, Mary vowed not to abandon her memory, exclaiming that “The grief, / and guilt, / and anger, / and truth / I feel about her death / weave into the characters of my book” (Judge, 2018, p. 247). Within the same year, the corpse of Percy’s estranged wife Harriet was found in the River Thames. Mary was beginning to fear that death may suffocate her. “I feel as if my own soul / is buried in their graves” she writes, “Grief would swallow me / if it weren’t for the story / still growing in my mind” (Judge, 2018, p. 252).

Figure 6: Mary Shelley and Death (Judge, 2018, p. 252, 253)

Mary’s Redemption

Mary Shelley experienced an unfathomable amount of suffering throughout her life, but Frankenstein as we know it may never have existed without these tragic events transpiring. When confronted with life’s sorrow, Mary could have succumbed to depression or even suicide, but she found a way to harness her devastation into creative energy to fuel her writing practice. In her darkest hours, Mary declared “I keep writing / until my pen scratches pain / as loud as screams” (Judge, 2018, p. 255). Catharsis is the psychological relief achieved by the expression of strong emotions such as fear, and scientific studies support writing’s therapeutic potential (L’Abate 1991; Pennebaker 1997). While Marry often lacked control over her circumstances, her creation of Frankenstein gave her a space where she was in total control of a narrative. In this way, authorship provides not only therapeutic potential but also a crucial sense of agency. Finally, the beauty of written word lies in its capacity to promote change across time and place. Anyone who has read an excellent book can attest to its power to inspire, challenge, heal, and, most importantly, transform our perspectives.

Figure 7: Mary Shelley and Freedom (Judge, 2018, p. 48, 49)

References

Judge, L. (2018) Mary’s Monster: Love, Madness, and How Mary Shelley Created FRANKENSTEIN. New York, NY: Roaring Brook Press.

L’Abate, L. (1991). The use of writing in psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 45(1), 87-98. doi: /10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1991.45.1.87

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x